Slow down. Steep your words in time, they’ll be better for it.

-Patrick Holland

Patrick Holland is a novelist and short story writer. He is the author of seven books, most notably The Mary Smokes Boys (2010), which was longlisted for the Miles Franklin Award and is currently being made into a feature film. His work has been recognised by awards including the Miles Franklin, the Dublin Literary Award, the International Scott Prize and the Commonwealth Writers Prize, and has been published, performed and broadcast in Australia, the USA, Hong Kong, the UK and Ireland, Italy and Japan. Patrick is currently Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Hong Kong Baptist University and divides his time between Hong Kong and Brisbane.

Author insight

Why do you write? The simplest answer: compulsion; the slightly expanded answer: a need to make sense of phenomena that puzzle and delight me; the esoteric answer: to salvage beautiful things from the decay of time.

What would you be doing if you weren’t a writer? An investment banker or hedge fund manager.

What was your toughest obstacle to becoming published? Getting published, both stories and books, came pretty quickly and easily for me. There are pluses and minuses to that. But at the end of the day, you’ve just got to convince a publisher, who is a human being such as yourself, that enough other human beings such as both of you will like the book or story enough to buy it to get the latter out of the sunk cost. In other words, just write something you yourself would be willing to pay money to read, and if you write it well, as long as you’re not very strange, there’ll be an audience for it somewhere. Making a book that will stand the test of time is another matter, but that’s probably a good enough heuristic for getting published.

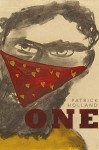

How involved have you been in the development of your book? Did you have input into the cover? I did get to give my thoughts on potential covers. I love nice cover art, for books, films, records… I’ve done some design work myself, and happily Transit Lounge has the best covers in the game. I think of them as something like the ECM Records of Australian literature. I love the cover of Oblivion.

What’s the best aspect of your writing life? The freedom to work anywhere.

—the worst? Honestly, it’s a privilege, there is no worst.

What would you do differently if you were starting out now as a writer? Take a little more time with everything – but when you’re young, ironically, you’re always in a hurry.

What do you wish you’d been told before you set out to become an author? Slow down. Steep your words in time, they’ll be better for it.

What’s the best advice you were ever given? For life generally: there’ll be good days and bad days, accept them equally. For writing: “Every character has to want something, even if it’s as simple as a glass of water”. I believe it was John Gardner who said that.

What’s your top tip for aspiring authors? As above, slow down, there are trillions of words published each year, don’t just add chaff to the silo. Rewrite, reimagine, leave things for a week, a month, a year, then pick them up and go again. Ignore the market, the fashions, mine your own experiences and the world you live in, really live in, not the one the television and newspapers tell you you’re living in. Write something so unique that if you hadn’t written it, it never would have been.

How important is social media to you as an author? Not at all to be honest. I appreciate that it can be a force for great good (even if it often seems to function as a thought homogeniser), but I just don’t engage much at all. I get a bit religious about this kind of thing, and I always remember that line, is it from the Gospels, or from one of the literary reduxs of the Gospels, but anyway “You’ll find him away from the crowds” , I’ve always admired and aspired to that – the idea that those most worth listening to probably aren’t going to be the ones shouting into a megaphone. I think of someone like Burial (aka William Emmanuel Bevan), making music with almost no fanfare that nonetheless changes the artform, or Satoshi Nakamoto.

Do you experience ‘writer’s block’ and if so, how do you overcome it? I’ve never experienced it, and if I did, the solution would be simple: I wouldn’t write anything. There are already too many published words, too much noise, I wouldn’t want to contribute to that without adding real value only for the sake of seeing my name on a publication or a modest cheque.

How do you deal with rejection? In writing? It doesn’t’ happen that often. In life, of course, frequently. But I’m 47, and in my 20+ years as a professional writer I’ve been told I’m a genius, the equal of Dante and Kerouac, and a low IQ bum whose books would best be employed as fire fuel. At this stage, I’ve heard it all, and I really don’t care. I don’t even care enough to develop a philosophy of dealing with it. What is valuable will last; what isn’t won’t. It’s independent of my concern.

In three words, how would you describe your writing? Minimal. Strange. Lyrical. (that’s how I hope it is anyway.)

If you had the chance to spend an hour with any writer of your choice, living or dead, who would it be and what would you most like them to tell you about living a writing life? It would be the first Gospel writer, Mark, whoever he was. Though I think I’d be frightened to ask him anything, lest my silly questions negatively influence arguably the greatest few pages of writing in human history. But, to bring things out of the mists of the ancients, I would spend an hour with the great Barry Lopez, whom I almost met about ten years ago but for a snowstorm that cut the road between Portland and Eugene. He died in 2020. He was one of my favourite writers of all time, and an unlikely supporter of my own writing. With Barry, gee, perhaps I’d ask him how he made those quiet little fictional miniatures he used to – in which almost nothing moved, something like literary still lives, yet they kept you entranced. But if things went well and he wanted to meet again, I guess I’d ask him to read my most recent novel and tell him to edit it as if it was his. That would be priceless. Then, before he left, I’d ask him if they tell stories in heaven, or is it unnecessary.

Book Byte

As the influence of the West falls away, an unnamed narrator drifts through the East’s floating world of non-places – chain hotels, airports, mega-cities – finalising often covert operations and deals. When he meets the enigmatic and beautiful Tien, a 21st-century floating world courtesan, he becomes involved with people and events that threaten his plan to escape life via various forms of oblivion.

Evocative and sparely written, in the tradition of The Mary Smokes Boys, this is a novel where the journey becomes the

story, filled with acute observation, desire and dreams.